Jupiter’s Legacy is a comic created by Mark Millar and Frank Quietly that intends to hold a mirror up to normal superhero conventions and show them where they fail. After the main series there were prequel comics (with additional art by Wilfredo Torres, Davide Gianfelice, Walden Wong, Karl Story, Ty Templeton, Rick Burchett, and Chris Sprouse) that go out of their way to show you the history that’s been idealized was broken the entire time.

Jupiter’s Legacy is a pretty incredible comic that does a good job using direct references as a shortcut to build an instantly familiar world that can be ripped apart at the seams guilt-free. The relationship between Millar and Quietly’s work and the work its based on isn’t integral to appreciating the story that they’re telling, but it’s key to understanding the full breadth of what they’re saying, and what they’re saying is a spectacular indictment of the way superheroes are revered.

It’s really good. It’s also… a lot.

If that sounds cool, it’s because it is. It’s coming to Netflix as a miniseries in May. Check out the trailer. If you like it, stop reading this, and come back after you’ve seen it.

It’s a culmination of everything Mark Millar has been working on/around since he first got on the American comic scene in the mid 90’s (he’d been working in British comics since the 80’s, but I haven’t read that so I can’t speak to them nearly as well). Dude has a penchant for taking classic characters and stuffing them to the absolute brim with political commentary, contemporary realism, post-modern examination, and general “wait, wtf” moments. He’s built a career out of taking something familiar and distilling it down to its most basic components while exposing them to novel situations that test the limits of their mythology.

He doesn’t find where characters break, he finds where their archetypes break, and then he smashes them to pieces.

Jupiter’s Legacy is probably his most complete work to date. I wasn't reading comics when it first released, but in preparation for the show’s debut, I wanted to check it out. Thankfully, I have a library card, and with that comes access to an app called Hoopla. From there, I rented the four volumes available now, recollected as The Netflix Editions. At first, I didn’t really care for the story, until I found out that the Netflix Editions collected the comics in chronological order, not release order. That turned me off since I thought the back half was infinitely more interesting, let’s jump into why.

Jupiter’s Legacy is a generational story about men and women who became superheroes in 1932, their children, and the repercussions of extraordinary people in an ordinary world. Powers don’t make problems go away. Pettiness, arrogance, piety, righteousness, arrogance, kindness, all these qualities are exacerbated by the powers they obtain and define them throughout the centuries.

Reading Jupiter’s Legacy isn’t reading one book, it’s reading twenty. And it’s watching ten movies. And sitting down for a few plays. And hell, it’s listening to a few albums, too.

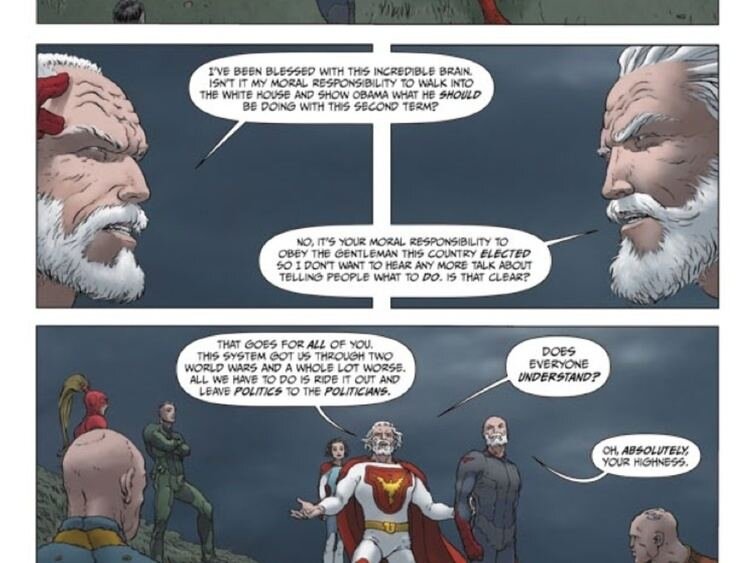

Art can’t exist in a vacuum. Everything influences everything else. Millar draws on so many inspirations to help build a realized world quickly, efficiently, and completely. Frank Quitely’s art has an appropriate classic and reverential feel when showing the older heroes, representing golden age stalwarts, and a gritty, post-modern edge in the modern/future segments. The artists who handle the flashbacks do a good job of making the direction look convincingly dated (see above image), and that tension between the story you expect because of the art and the narrative you get because of the story jarring and effective.

There’s a whole subplot in early issues about J. Edgar Hoover trying to blackmail a gay hero, The Blue Bolt, into revealing the secret identities of his teammates. That is a completely believable story but not one that ever could’ve been told contemporaneously. A book like this has to exist because our rose colored glasses need to stop painting the past in black and white, we need to see the gray that was always there.

Intertextuality sounds like a really big word that requires studying but it’s much more simple than it sounds. As I understand it (to the best recollection of my film school days), it’s about the relationship between different texts. That’s it, that’s the whole idea. Here are some examples:

1999’s 10 Things I Hate About You is a modern Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew

The X-Men reflect the civil rights and minority rights struggles in the United States

Weezer’s Teal Album is all cover songs

If you’re rolling your eyes and saying “it can’t be that simple, I must be missing something” it is that simple and you’re not missing anything. Intertextuality is an encompassing word that gobbles up a lot of other things. What’s the difference between something being intertextual and something being an allusion, or just, like, a reference? Intertextual works owe their entire existence to something else, an allusion can get by with a mention of something else, the work doesn’t depend on anything but itself. If you’re asking yourself what the significance of this, and I get that.

It seems meaningless, but what it’s really doing is building a language, one where certain verbiage is familiar but twisted to have new meaning, otherwise it is meaningless. Let’s go back to songs for a second and take a look at one of my favorite original/covers and their music videos, since music videos might be the one art-form I like more than comics.

Released in 1994 by Nine Inch Nails, Hurt is a somber account of Trent Reznor, then 29, looking at his life and analyzing what he’s becoming as he ages. What have I become?/My Sweetest Friend/Everyone I know/Goes away in the end when you’re 29 sounds like you’re becoming a dick and driving everyone away.

Released eight years after the original in 2002, Johnny Cash, then 72, released his cover of Hurt one year before his death. Besides changing the line from I wear this crown of shit to I wear this crown of thorns (itself an intertextual reference to Jesus leading up to his crucifixion), Cash recording this near the end of his life simply carries a different weight that Reznor was unable to apply to the song. What have I become?/My Sweetest Friend/Everyone I know/Goes away in the end hits different when you’re 72 and you’ve lived the life that Johnny Cash did. The fact that one of Country’s most beloved and enduring country stars transforms an Industrial Rock ballad into one of his biggest hits (let’s face it, it’s Johnny Cash’s song now) is necessary knowledge to know just how powerful a musician Cash is.

So, why does any of this matter, and why is it important to Jupiter’s Legacy? Because Superman can’t die, Batman will always be 25-34, Reed Richards is the smartest man in the universe but his earth will always looks more or less like ours, Spider-Man has been broke with bad luck for 60 years. These characters impervious to change, despite the fact that they’re decades old. The same stories are being told now that were 40 years ago, with finer details changed along with post-modern, post-structuralist, trans-humanist flairs to reflect the zeitgeist.

That’s where Jupiter’s Legacy shines. The Utopian as a character isn’t Superman, and Lady Liberty isn’t Wonder Woman…

But, c’mon. That’s Superman and Wonder Woman. If that wasn’t clear visually, they certainly hammer that point home in the story.

I’m going to dive a little deeper into the story now so if you haven’t read the series yet, or if you’re holding out for the Netflix show, you should bounce now.

The flashbacks are a particularly sobering realization about what works in the Superman mythos and what doesn’t. As readers we understand the dude is perfect and little details (he takes his Lois Lane out to dinner in a different city every night, whenever they have sex he always makes sure she orgasms multiple times before he does, he made her engagement ring out of carbon with his bare hands, flew her to one of Jupiter’s moons for their anniversary and created a pocket atmosphere where she could breathe without a helmet, and a thousand other things) make him not just a Superman to the world, but a Superman to her. Despite the tremendous effort he puts into his relationship, it fails, because she can’t stand how perfect he is. She spends her days not being as incredible as he is and that pushes her to the breaking point where she wants out.

He eventually finds love with Lady Liberty, a fellow hero gifted powers by the same alien species that made Sheldon Sampson The Utopian, being a comment that someone like Superman who is so beyond humanity couldn’t possibly connect with them in any meaningful way. Only someone on equal footing as him really has the opportunity to be with him, and in the story, they’re able to conceive (further highlighting the incompatibility with his previous partner who was unable to bear his children) and they create part of the second generation of power endowed heroes…

Who are so fucked up it’s hard to look at sometimes. Chloe, their daughter, lives the life of a despondent socialite, like some kind of super social influencer, who perpetually overdoses on drugs while not applying herself to anything meaningful. She’s near-invulnerable, with a powerful sonic scream. Brandon, their son, is an insecure, arrogant telekinetic who’s arguably more powerful than his father, but with none of the moral direction that made him The Utopian. Both live in the shadows of their parents, unable to measure up to what they’ve accomplished. Chloe doesn’t date superheroes because she says it’ll be like dating her father, so she’s often more attracted to supers with ties to the villains of the world. Brandon feels abandoned by his father, who was always off saving the world.

All the real super villains of the world have been defeated, but society still teeters on the edge of collapse. The Utopian’s brother, Walter, aka Brainwave, begins to interject himself into base-human politics in an attempt to fix an economic downturn that was occurring. The Utopian, doesn’t think it’s a good idea, despite Walter’s insistence that it’s necessary.

This assertion by the Utopian, is Millar highlighting a weakness of Superman, one of his few. He’s idealistic at the expense of humanity, believing he should really only save them from things they can’t deal with directly. An alien invasion? Humanity’s not equipped for that. A global recession? Dude that’s not what we’re here for, you gotta bounce. Sure Superman saves cats from trees, but if the guy Is so smart and so powerful, why doesn’t he reverse the desertification of the Sahara? Why doesn’t he use his heat vision to desalinate ocean water to end drought conditions? Why is he only punching things?

This is what really sets Brainwave off. The dude is a psychic who’s basically a stand-in for Charlies Xavier from the X-Men comic, or Martian Manhunter from the Justice League. He’s an extremely powerful telepath who can separate people’s minds from their bodies so completely that they can’t even feel what’s happening to them physically. On top of being able to manipulate people with his powers, he’s just a super manipulative dude in general. He used his powers to steal the wife of a teammate, and he used Brandon’s insecurity to turn him, and other children of heroes from the first generation, against The Utopian and Lady Liberty. In pretty gruesome fashion.

Brandon kills his father at the suggestion by Brainwave because The Utopian’s ideals and philosophies are incongruent with the 21st century. Alexander wept, for there were no more worlds left to conquer. All the villains were dead, so the heroes became their own enemies by inaction and complicity in a status quo that was deteriorating for the world at large. There came a time when the old gods died! Through the story heroes are redefined in a realistic way that reflects geo-political ends and the power to affect change beyond petty crime on city blocks or alien invasions in the countryside. This isn’t passive ideology and symbolism, this is the war of ideas being fought, with real winners and real losers.

That sounds like an interesting story, but an even more interesting statement when you realize that means even Superman will lose his relevance with the world around him. Reading the story gives you the most impeccable and precise sense how the story is happening and what in the story his happening. Intertextuality is key to understanding why it’s happening, and what the significance of the happening is. What I’ve shown you is really just the beginning the of the story, there are dozens of references, allusions, and intertextual callbacks that range from The UN G6 to the Gods of Olympus to Star Wars, and scores of others. Like I said this isn’t like reading one book, it’s reading twenty.

Jupiter’s Legacy does what DC and Marvel could never do; it lets the heroes affect change in a world and react to the permanence of their decisions. It tells the story of generations growing, resenting, destroying, and rebuilding in a way the big two never could.

Pretty cool that batman is still an asshole even when he’s not batman, right?

If Marvel and DC are a growing mythology, then Jupiter’s Legacy is a completed myth. Things don’t reset to zero for the next story, because that’s not how it’s formatted. By comparison, ongoing stories are more akin to plays, where at the end of an issue they go back to their marks in time for the next creative team. You don’t need to read every issue of Superman to know the Utopian is supposed to be him, and thankfully the pervasive nature of superhero iconography has made it something most people speak casually. It’s part of the lexicon at this point.

Each text you recognize breathes an entirely new context into the story, and it’s key to understanding what Millar and Quietly are really trying to say with Jupiter’s Legacy, and makes it a completely different story. It’s impressive as all hell, the creative team really went above and beyond in taking these characters that were immediately familiar and saying something with them that’s definitive. I cannot recommend you check it out enough.

Even more impressive? I barely talked about Chloe at all, and she’s one of my favorite new comic book characters in years.